The ghost town of Charleston is located in Arizona’s southeasternmost county, Cochise.

In its heyday, Charleston was a thriving place serving as the business center and residential district for the silver mills just across the river. Millville, as the mill site was called had been founded first, but it wasn’t long before Charleston sprang up on the flats on the opposite banks of the San Pedro.

San Pedro River

History of Charleston, Arizona

Ed Scheiffelin, the man who made the great Tombstone silver strike, was indirectly responsible for the creation of six towns along the San Pedro River. These towns would serve as mill locations to process ore from mines in the district.

Charleston was to be the first of these mill towns when in 1878 Scheiffelin made arrangements for the construction of a stamp mill to process the Tombstone ore.

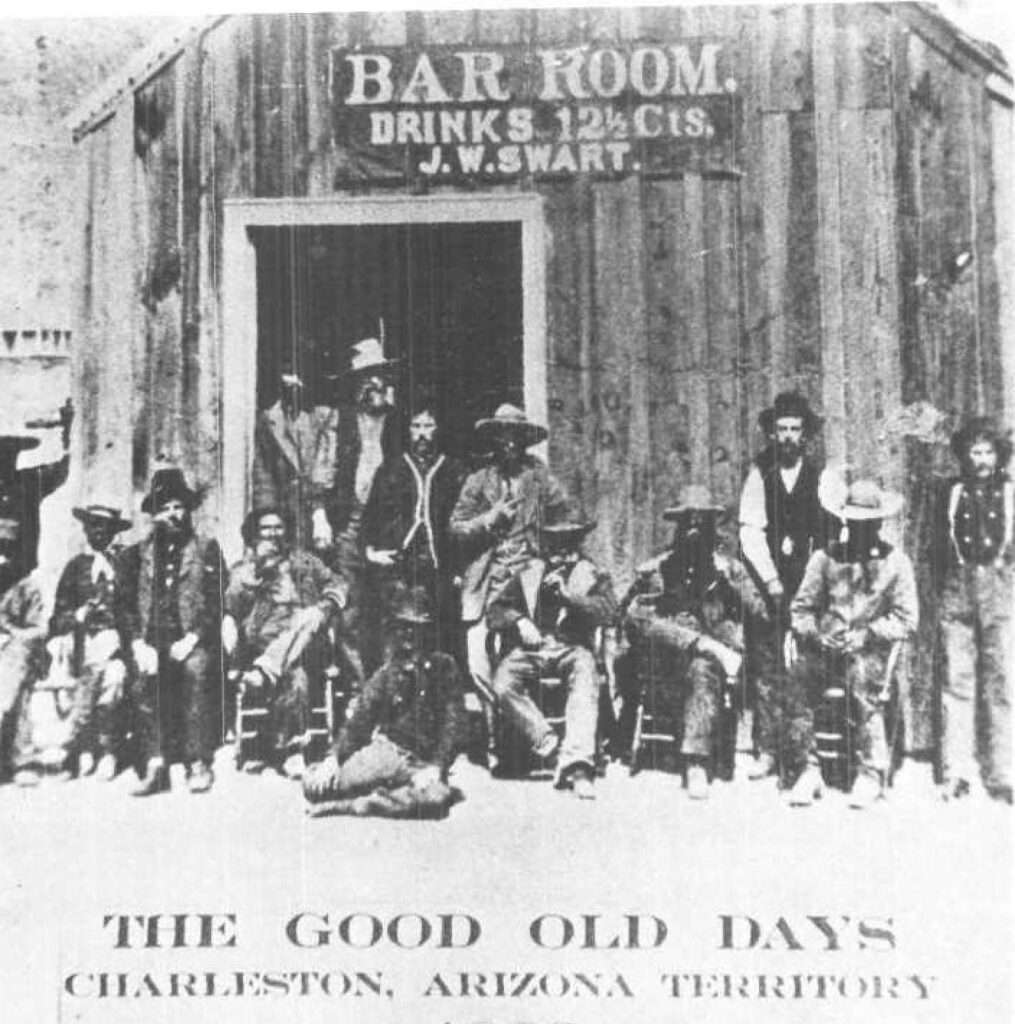

The nearest water to drive the mills was eight miles from Tombstone to this point on the San Pedro. Flow from the river was used to power the huge stamps that would crush the ore from Tombstone. In 1879 a post office was established at Charleston and during the 1880s the town grew to more than 400. There was the usual assortment of saloons, hotels, general stores and restaurants, a school, church, blacksmith, physician, and meat market.

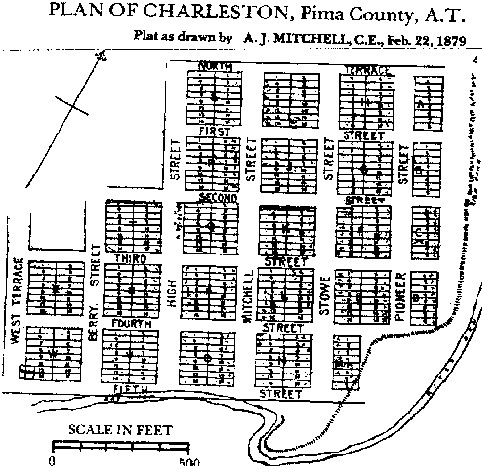

Charleston was officially surveyed on February 1, 1879. Amos W. Stowe, to become a future merchant of Tombstone, claimed 160 acres on the flat across from the mills for agriculture and grazing.

Why the town was named Charleston is a fact not apparent in any historic records. Stowe was a generous man and leased lots for three years to anyone interested in residing in the town. He charged nothing for the leases. According to the Arizona Citizen, there were about 40 buildings in Charleston by May of 1879. Most were adobe. The town had 26 blocks and had been surveyed with each block having 16 lots. The north-south streets were 80 feet wide and those running east-west were 50 feet wide.

An interesting historical fact of Charleston was how and where timber was acquired for the construction of the mills and some of the town buildings.

According to historic accounts in the Arizona Citizen, a sawmill was constructed in the Huachuca Mountains. Richard Gird, a partner with Ed Scheiffelin in the mills, purchased a complete sawmill and had it shipped from San Francisco by ship around the tip of Baja

California and up the Colorado River to Yuma. From Yuma, the equipment was transported by wagon to the Huachuca Mountains and assembled. When completed, the sawmill was 12 miles from Charleston and milling operations began on January 14, 1879.

Like any town based on a single economy, Charleston lived and died with mining. When the mines of Tombstone flooded and operations stopped, Charleston quickly faded from the scene. On October 24, 1888, the post office was discontinued.

After most residents moved out, Mexican squatters took up residence until nature reclaimed the land. Charleson’s final blow was during World War II when soldiers from nearby Fort Huachuca used the town as a battleground to train for combat.

Charleston’s history was colorful. It was reputed to be the hangout for many of the Southwest’s badmen, including the Clantons, Johnny Ringo, Curly Bill, Johnny-Behind-The-Deuce, and others.

The Clantons in Charleston, Arizona

Ike Clanton owned the first hotel in Charleston, a canvas building that was rented and used until more substantial structures could be built.

In 1880, Newman Clanton bought Clark & Griffin Liquors, a saloon. Included in the purchase price of $200 were all the liquor, bar fixtures, and two other town lots. The two lots were reportedly located on the west side of Pioneer Street.

In 1881, Clanton again bought a property in Charleston. This time a residence on Stowe Street, Lot 6 of Block M, Plan of Charleston. The house on Stowe St. was the residence of Fin Clanton during 1881. As it was of probable adobe construction, the Clanton house on Stowe Street has long since melted into the desert sands.

The violence that seemed to thrive in so many western towns was not a serious problem in Charleston. Perhaps it was because Charleston was a working town. With the mills just across the river and the sole economy of the town, there was little to attract much of the trouble common to places like Tombstone.

Charleston, Arizona today

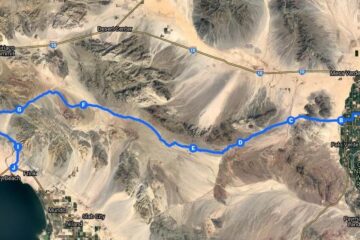

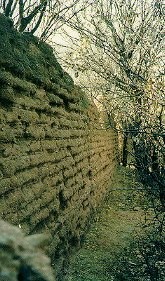

Today very little is left of Charleston. A few adobe walls stand rounded and ragged against the elements. To visit the ruins, drive the paved Charleston Road from Sierra Vista or Tombstone to the railroad tracks beside the San Pedro River. From here you can park and walk downstream about a half-mile to an overpass. The river is shallow and safe at this point and you must cross to reach the ruins. Before crossing, the ruins of the old mills at Millville can be seen on the hill to the northeast.

To enjoy Charleston you will have to come prepared to let your mind wander. There is little left to tell of the life of this town, but careful examination can turn up small bits of the past for a fertile mind to ponder. We sat on a dirt pile beside a crumbling adobe wall to enjoy our lunch. Here we found bits of decorative dishware perhaps abandoned by the owner when she left to seek life somewhere else. Broken bottles, stained deep purple by thousands of days in the sun, litter the ground.

To enjoy Charleston you will have to come prepared to let your mind wander. There is little left to tell of the life of this town, but careful examination can turn up small bits of the past for a fertile mind to ponder. We sat on a dirt pile beside a crumbling adobe wall to enjoy our lunch. Here we found bits of decorative dishware perhaps abandoned by the owner when she left to seek life somewhere else. Broken bottles, stained deep purple by thousands of days in the sun, litter the ground.

This area is within the San Pedro Riparian area and no vehicles are allowed off of the established roads. The ruins are a good hike from the parking area, although the trails have been improved by the BLM in recent years. Give yourself lots of time for the round trip. Relic collecting, metal detecting, or removal of souvenirs is illegal.

Do you like to camp out when exploring ghost towns and old mining areas? See How to find places to park your RV, go boondocking and camp for free.