This is a lost mine story of an incredibly rich gold ore, located somewhere along the south slope of Arizona’s rugged Harquahala mountains. The desert southwest has many stories of lost mines, some more believable than others. This one has quite a few historical facts. You be the judge.

The story starts over 150 years ago and centers on an Indian squaw named Cachie.

Now Cachie was the daughter of a Yavapai Indian chief. Apparently when she was quite young, her father showed her several rich hard rock gold deposits, he told her to tell no one, except her future children.

Cachie had a deformed foot, called a club foot back then. The squaws of the Yavapai had to pull their weight, and if not they became outcasts. Cachie was no exception, even if the daughter of the chief. She was subjected to taunting and ridicule by her own people. She was sent to an Indian school in San Bernardino, where she learned to speak, read and write both Spanish and English.

Upon returning to her reservation home several years later, still an outcast, she began doing domestic work for some of the nearby settlers. As the years passed, Cachie realized she would probably always be alone and childless.

She was taken in by a miner named Charles Genung and his family. Now Genung was liked by the Yavapai, who were known as a friendly and peaceful tribe. He hired them to help at his mine, when no one else would.

This was the time of Apache Indian uprisings and raids on white settlers and miners. Genung hosted meetings at his property with US Cavalry General George Crook, and Cachie’s father, the Yavapai Chief, where Cachie acted as interpreter.

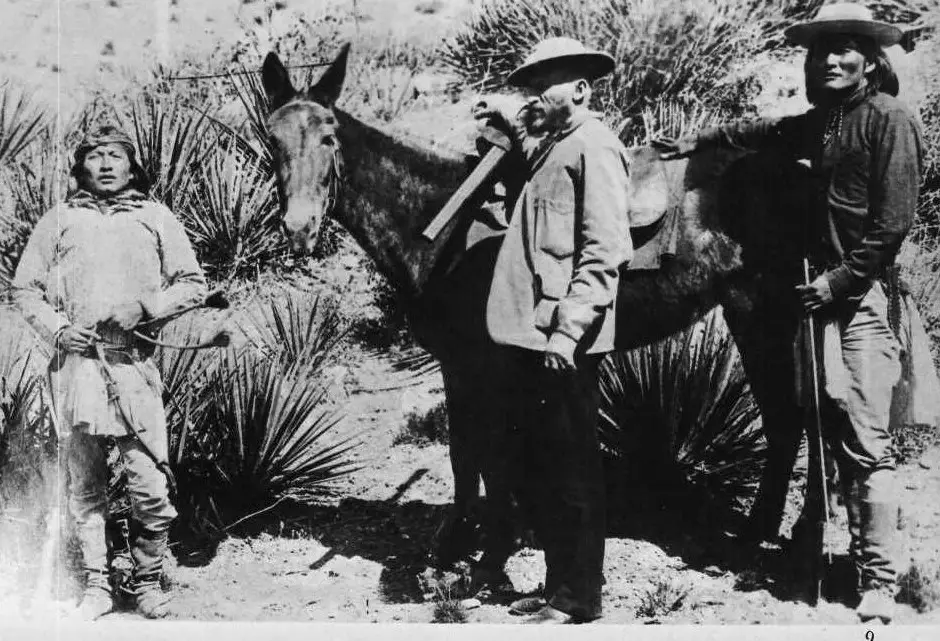

General Crook with two of his scouts at the time of the Apache uprisings

As a reward for his help to the Yavapai, and with her father’s permission, Cachie revealed to Genung the location of one of the gold deposits. Genung apparently dismissed this ore, because it appeared to contain mostly copper pyrites.

It wasn’t until nearly 20 years later that he realized the error of his ways. The source of that ore started one of the biggest gold rushes in Arizona history, producing over $15,000,000 in gold. The Bonanza and Golden Eagle veins alone produced over $3,000,000. This was the first gold deposit Cachie tried to give away. But not the last.

When the Genung family moved away Cachie returned to the reservation and the continued taunting of the squaws. With her health declining, she was taken in by a Mexican family named Valencia .The Valencia’s took her to live with them at their home near La Paz, the mining town near the Colorado River.

Maria Valencia nursed her back to health. Cachie would help with the household chores, and would help tend to the children of a neighboring family, the Ochoas.

To repay the kindness of the Valencias. Cachie revealed the location of another hidden gold deposit. Mr. Valencia accompanied Cachie back to the Harquahalas, where they followed animal trails high up into the mountains to the source of the gold.

Now Mr. Valencia was not a prospector and the ore here looked nothing like the ores back at the Colorado River mines. Once again a rich ore was dismissed. This ore was to become the fabulously rich Golden Eagle vein of the Harquahalas. A nearby watering hole bears the name Cachie’s Tank even to this day.

Old building near the Harquahala townsite

The years passed, Cachie’s health declined. She lived in an abandoned miners cabin. Occasionally, Pete Ochoa, one of the children Cachie tended when she worked for the Valencia Family, would stop by and give her medicinal herbs, and check up on her.

Pete Ochoa was 19 now and a freight driver on the Ehrenburg to Prescott route. Cachie one last time revealed a rich hard rock gold deposit to a caring friend. Cachie had become somewhat of a legend because of her gold finding knowledge, so Pete readily agreed to go with her to find the rich ore.

When Pete returned two weeks later, outfitted for the trip, he found he was too late. Cachie had passed away.

The story now gets cloudy, probably because most of it was related by a relative of Pete Ochoa, who didn’t want to disclose too much information. The Ochoa family searched for the lost gold for several years.

As late as the 1970’s Ochoa’s grandson was searching the south slopes of the Harquahalas with a metal detector. What we do know is that the ore was an odd looking, rusty, oxidized quartz. When broken up with a hammer, the quartz would fall away, leaving masses and wires of gold.

There are a couple more references to this rich ore, one in an article from the Yuma Sentinel in 1892. It tells the story of two French prospectors, who, 20 years earlier came into Yuma, loaded down with a rich rusty ore full of gold. They deposited the gold with the Cooper company store. Reportedly about $8,000 worth.

They spent a few nights at the saloon, purchased supplies and headed back out. After spending the night at Aqua Caliente, they realized they were being followed by some of their saloon acquaintances. They managed to elude their followers north of Agua Caliente.

The south slope of the Harquahalas lie about 40 miles north of Agua Caliente. The Frenchmen were never seen or heard from again, and their gold remained on deposit at the company store until it changed hands 20 years later.

Another account of a rusty high grade quartz was related by George Sears, old time Ajo mine owner. While on a trip from Phoenix back to Ajo he decided to detour into what he thought were the Eagletail Mountains.

Stopping to check an old prospect hole, he picked up about 25 pounds of ore to balance the pack on his mule. After a day and night spent in camp because of rain and flash flooding, he gave up the idea and headed back to Ajo.

Upon arriving home he discovered that the ore he was carrying was full of gold. Sears was never able to find that prospect again. The Eagletails are just south of the Harquahalas.

Today the north end of the Harquahala Mountains and the Eagletail Mountains are Wilderness areas and closed to prospecting and mining.

The south side of the Harquahalas and the Little Harquahalas are open BLM lands, and as such are open to prospecting and mining.

This is a popular spot for drywashing and detecting for gold. If you decide to visit the area, to look for Cachies’s lost high grade, be sure to check land status as there are a lot of active claims, both lode and placer.

I have a post which will help you to check land status here.