I first came across the story of the Lost Emerald Mine of the Santa Rosa Mountains back in the 1980’s in a guidebook to the Anza Borrego area of Southern California.

Years later I found the complete article in the December 1948 issue of Desert Magazine. Written by Marshall South. a regular contributor and a controversial figure of the day, shortly before his death. It recounts a trip he made to find the mine in the early 1920’s

Keep in mind that the Anza Borrego State Park and the Santa Rosa Mountains National Monument are completely off-limits to collecting of any kind. Which is how it should be I suppose.

This area of Southern California is number 7 of the top 10 largest roadless areas in the US outside of Alaska. I’ve hiked the Rockhouse Canyon area and believe I’ve seen the far off landslide mentioned in the following story. If you are going to explore the wild, here are some posts you may find helpful.

First Aid kits for prospecting, exploring and remote camping

How to find gold – Area research – To help you find areas that are open and closed to prospecting or collecting

Satellite communicators, GPS messengers and personal locator beacons (PLB’S)

Here is the story of The Lost Emerald Mine of the Santa Rosa Mountains.

Will the old Indian emerald mine in the Santa Rosa mountains bordering Borrego valley ever again be reopened and worked? That is a question which I have asked myself many times, particularly during the last few days. Probably the answer is “NO!” But quien sabe? Perhaps I attach too much importance to the words of old Pablo Martinez. And anyway I have been accused of being superstitious. But you shall form your own conclusions.

This old Indian mine truly belongs to the class of lost treasure. But it is lost only because I doubt if it is within the power—or at least the profitable power—of white men to recover it. It is one of those things which Nature has taken back unto itself. Comparatively few people, I think, have ever heard of this old gem mine.

The legend is not as well known as that of the Pegleg or the Lost Arch and other will-o-the wisps which have taken such hold upon the imagination of South westerners. Nevertheless the emerald mine perhaps more rightly deserved a first place than any of these.

Emeralds—good emeralds—are rare. And there are comparatively few emerald mines in the world. This one—the one in the Santa Rosas—is, judging by the claims of legend, probably the only one of its kind in the United States.

The story of the old mine has always fascinated me. Perhaps because it was so very difficult to learn anything definite about it. Yet I have never had any real doubts as to its existence. Several individuals have tried to find it. And some have come very close. One who put his hands—or rather feet—closest to the location was the late Bob Campbell, old-time resident of Borrego Valley.

Bob—who had a generous proportion of Indian blood in his veins—almost found the mine. On the last lap of his search, something stronger than hope of wealth deterred him. “I am afraid,” he said simply. “I cannot go on. The spirits of the old people do not want this mine discovered. I must go back.”

His companion protested and argued. But Bob was obdurate. He turned back. The search was abandoned. The old mine, which legend says had been worked from the earliest times by the desert Indians, who had a trade route for the gems down into Mexico and beyond, was again left in its shroud of mystery. So, through a number of years, the thought of this mysterious Indian gem deposit has held my interest.

Several times I have been on the point of setting out to hunt for it. But always something intervened. Recently, however, the opportunity came. In company with Robert Thompson, a South American mining engineer, I went in search of the mine.

We were not alone. Thompson, who came from the southern republics several months ago on an extended vacation, had found somewhere an ancient Indian, Pablo Martinez. Pablo who was very old and hailed originally from Hermosillo, Sonora, averred that his great grandfather had been one of the workers in the emerald mine.

Stories concerning it had been handed down, he stated, from father to son. Some of these stories, to which I listened, obviously were fantasy based on a slender thread of truth. But there were others that sounded convincing.

Thompson knows emeralds—the Republic of Colombia, where he operates extensively, produces many of the worthwhile emeralds of the world. Also, he knows Indian psychology. We set out on our trip with high hopes. There wasn’t anything particularly mysterious about the initial part of our trio.

We wound down through Borrego Valley and across Clark’s dry lake. The base for our search was to be Rock House Canyon as it had been for Bob Campbell and the various others who had preceded us. We took the car as far as we could, parked it and made camp for the night. The next morning with canteens and light packs the three of us set out on foot.

Rock House Canyon and the site of the Rock House deserves some mention in its own right, for it is an interesting spot with an imagination-stirring atmosphere all its own. But I cannot spare space, at this time, to devote to it. Our quest lay beyond, among the precipitous slopes and barren ridges.

Without delay we struck off into the savage, upended terrain. We were not traveling entirely blind for by diligent sifting of all the reports which I had been able to unearth, I had some idea as to where to head in.

Old Pablo began from the first to justify our rosy hopes. Either he actually absorbed a lot of information from family legends or else he was acting under some sort of an uncanny inherited sixth sense. At any rate he seemed to know his business. He led off oddly in the manner of a man who knows just where he is going.

He was astonishingly wiry despite his years—scrambling up over rocks and ledges with the agility of a mountain goat. From time to time he would pick out old Indian trail signs that neither Thompson nor I would have noticed.

We began to feel curiously elated. The grip of a strange excitement mounted in us. Nevertheless it wasn’t going to be as easy as all that. As the rugged tangle of the mountain increased we began to realize this.

Desert mountains are heartbreaking, especially under a hot sun. Everything was thirsty and barren and the glare hurt the eyes. Doubling up gullies and floundering across interminable ridges began to confuse us. We were tired and our nerves were getting jittery. Pablo lost his agility and began to lag well in the rear.

As the day wore on he became either confused or sullenly unwilling. “A ridge with rock formation on it that looks like a castle” had been part of the vague information. But all the rocks looked like castles. The upthrust of weird boulder-shapes against the skyline was bewildering.

We made a camp at dark in a lonely depression between desolate ridges. I, for one, had the feeling that we had circled aimlessly. We were all depressed. At least Thompson and I were. Pablo said nothing.

The stars were points of yellow fire against black velvet. And the thin wind that came down from between the ridges was lone and chill. I fell asleep listening to Thompson telling a yarn about searching for an emerald mine in the Andes. I didn’t hear it very well. I was disheartened.

I slept badly. It seemed to me, in my dreams, that the lonely canyons about us were peopled by a myriad of ghosts. Brown ghosts. Unfriendly ghosts.

Several times I awoke in a cold sweat. Pablo was restless too. Only Thompson seemed to be sleeping soundly. He is a practical man and has little use for spirits.

We were aroused to a chill and cheerless start well before sunup. We had a cold breakfast. Our enthusiasm of the day before had all evaporated. And then, all at once, and not a hundred yards from the spot where we had camped, we came upon the Indian trail sign which marked the terminus of Bob Campbell’s attempt. I recognized it at once, from what had been told me.

Two big brown rocks, set one upon the other, with a smaller white stone on top. And off to one side a couple of tall boulders leaning together at the tops like an inverted V. I gave a shout of triumph that brought Thompson running. Even Pablo brightened up. His old enthusiasm returned. He began to jabber excitedly in Spanish.

After that things began to go better. It was as though we had turned some sort of corner. I don’t know what it was. But I think it was principally Pablo. He had changed. He shuffled around a bit, scanning the ridges against the skyline. Then he started off at his old wild goat lope—and in a direction totally different to that which common sense would have dictated for us.

“Look now for un cabeza del lobo,” he grunted. “Way up. On top.” But it was not on top of a ridge that we eventually found “a head of the wolf.” It was way down in the bottom of a steep gully. It was a mere chance that caused Thompson to glance at the fallen rock mass. But as he did he gave a yell of excitement. “There’s your wolf head,” he shouted. “Look down there! Wrong end up!”

It didn’t take two looks to prove he was right. The outline of a wolf’s head was unmistakable on the rugged mass, even in its upside down position and with the clutter of fallen stones that lay piled around it.

Thompson’s practiced eye was sizing up the opposite slope. “Earthquake,” he said briefly. “The old boy was right. It has been on the top of the ridge. But a heavy earth shock must have toppled it. And there, if I’m not badly mistaken, is your mine. Goodbye emeralds!”

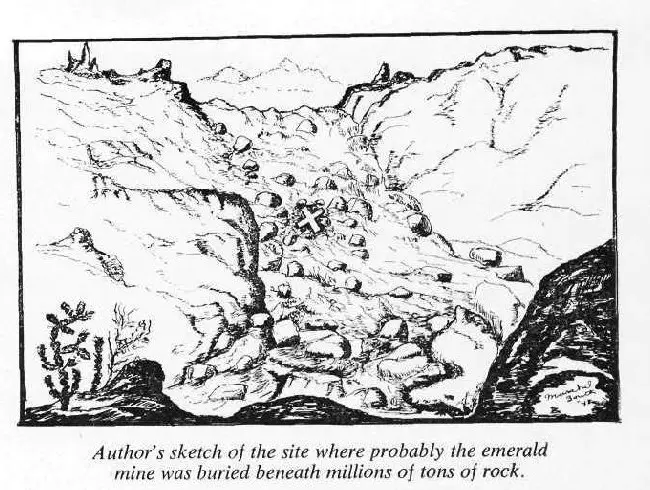

He was pointing. And following his leveled finger my heart sank. An earth shock, and a heavy one, had done it, without doubt. All the slope opposite was a cascade of smashed rock and jumbled boulders. The old emerald mine, if it had been, as Pablo had averred, below the wolf’s head was now hopelessly buried beneath millions of tons of rock and earth.

And as we stood there, stunned by the realization, we were aware of old Pablo, skipping and scrambling up over the fearsome slide like a malevolent billy goat. About half way up he sat down and pointed to the rocks at his feet: “Aqui!” he shouted down to us, “Aqui, senores!

Here is where was la mina. But make not the false expectations. The emeralds are still here. But they are not for the white man. This is a curse from the old people. The mine will never be worked again except that it be by the indios.”

There was a sort of wild, fierce triumph in his cracked voice. At that moment he looked less like a wizened old man than some spirit of his people, gloating at our disappointment. But just then we were both too dejected to pay much attention.

We spent most of the rest of that day searching the vicinity. We uncovered evidence enough that here, in all probability, had been the ancient mine. We found pottery sherds in plenty, and fire traces of old camps.

In one place, where the sliding rocks had swept aside its earth covering, we found an old burial—an ancient grave. And amidst the bits of age-weathered human bone something sparkled like a bit of green glass touched with flame.

Thompson pounced on it. “Emerald,” he exclaimed breathlessly, “—and of first quality! Look!” He shoved it at me, along with his pocket lens. Yes, it was an emerald all right. Small but fine.

And in the hollow where the bones lay we found also bits of pale green mineral—beryl, the substance emeralds are found in. We had found the site of the lost emerald mine of the Santa Rosas. The decision was inescapable.

But much good it did us. Here was the mine—”Here,” as old Pablo said, pointing downwards. But hundreds of thousands—perhaps millions—of tons of rock lay above the primitive workings. Where would come the machinery and the money to heave aside all this disheartening, monstrous overlay? And in the end, perhaps, draw only ablank. Another disappointment.

“For you never can tell about an emerald mine,” Thompson said. “Emeralds go in ‘pockets.’ And the old timers may, after all, have worked it out. You never can tell.” Yes, you never can tell. Nor will anyone now, I think, ever tell.

Well, we had the fun of finding the lost emerald mine of the Santa Rosas. But the irony of it is that it is still lost.

Lost mine area? Google Earth screenshot of a slide area on the south slope of the Santa Rosa Mountains.

More lost mines – Lost Gold of Mono Lake