Also known as the Lost Cement Mine

This is a newer version of a lost mine story related by Mark Twain in his book “Roughing It,” and also in W. A. Chalfant’s “Gold, Guns, and Ghost Towns.” It is the legendary Lost Cement mine, and so far as the records show it has never been re-discovered.

Neither man’s name seems to have been preserved although their activities are frequently mentioned in old records of the Mammoth Canyon discoveries.

The most authentic of these writings seem to be those of J. W. A. Wright, who wrote from Mammoth in 1879, reported for the San Francisco Post on the searches still going on for the lost cement mine.

Indian trouble

IN THE YEAR 1857 the trails to the goldfields of California were more or less well defined. Indians were still one of the major obstacles. Not long after the massacre of 140 people at Mountain Meadows, a band of fast riding Paiutes intercepted a party of California-bound settlers several days’ march west of the massacre scene. The party was following the old Spanish Trail.

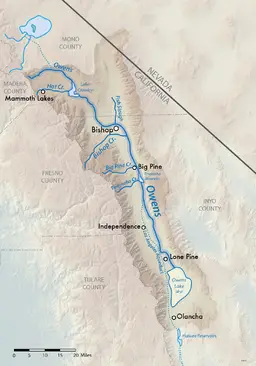

In the ensuing fight, the settler group became disorganized. Two men of the party escaped and in the darkness, that night struck north. The scene of the battle was roughly on the California-Nevada border. Traveling by night and hiding by day they kept a northerly course up the wide desert valley in which they found themselves, hoping to cross the trail of other parties traveling west.

To the west, they could see the towering mountain ranges they would eventually have to cross. When their water gave out they turned westward and finally arrived at a clear, cool stream. They had struck the headwaters of the Owens River.

The original discovery

A short time later, in the same general vicinity, they were resting near a small valley within sight of a lofty gray mountain. One man broke off a piece of a cement-like ledge and found it spotted with yellow flakes. He was convinced the yellow stuff was gold. His partner laughed at the idea, insisting the yellow flakes were worthless. The believer filled his pockets with about ten pounds of the ore and the two went on their way.

Eventually, they made their way across the mountains and found a small stream that led them to the San Joaquin River. They followed the San Joaquin to the settlement of Millerton.

The man with the gold made plans to retrace their steps to the rich ledge. However, he had become ill and before his plans were completed he was forced to seek treatment in San Francisco. His condition became so bad he had to give up any idea of returning to the treasure.

Doctor Randall

Indebted to his physician, a Dr. Randall, and without funds he paid what he could with the ore he had left and gave Randall a map of the section containing the gold-bearing ledge. The man died soon afterward and nothing more was ever heard from his companion.

Doctor Randall arrived on the scene in the spring of 1861. He headquartered at old Monoville and hired a party of men. Next, using the dead man’s map as a guide, he located a quarter section of land a few miles north of the town on what was known as Pumice Flats.

Not far to the northeast were the Mono Craters. The cones, as well as much of the surrounding area, were coated with pumice from the once active volcanos. Randall hired a man named Gid Whiteman as foreman of eleven men and began the task of prospecting every inch of the 160 acres.

Van Horn and the German

The following year, 1862, a man named Van Horn joined the search. He seems to have been prominent in the mining fields since one district was named after him. Another member of the searching party was a German whose name has not been preserved in the records. The German is now believed to have re-discovered the gold-bearing cement ledge, though not on Randall’s 160 acres.

He took Van Horn into his confidence and the two quit the search together, saying they were tired of the country and wanted to seek new fields. They took one horse belonging to Van Horn to carry their belongings and left in the direction of Aurora.

Once hidden from the others they went to where the German had found the ledge. They loaded the horse with sacks of ore, concealed the location, and struck out for Virginia City. At the Walker River, they crushed and panned the cement-like material, obtaining several thousands of dollars in gold.

In Virginia City, they bought needed supplies, tools, and horses and took a third man into the partnership. Back at the location, they started work on what was intended to be a permanent camp.

Joaquin Jim

The work was barely begun when Indian Chief Joaquin Jim raided the camp with a party of braves, took all their supplies, leaving only the clothes they wore and one horse with which to get out of the country. The three returned to Virginia City to wait for the Indian troubles to subside.

In the meantime, Van Horn became the victim of an ailment that left him semi-invalid. He started to San Francisco for treatment but on the boat from Sacramento became so ill he feared death was near.

He confided in a man named Carpenter, adding that he believed his two partners were planning to return to the ledge despite the Indian menace.

Kirkpatrick and Colt

Carpenter himself made no effort to enter the search but his knowledge was passed on to two men named Kirkpatrick and Colt, the latter a member of the firearms family.

These two men came to Monoville, hired a guide to take them to the vicinity of Mammoth Canyon where they believed Van Horn’s camp to be. The search uncovered a place where logs had been laid for a floor and nearby were the stumps of trees that had been felled.

Continuing the hunt for the ledge the men found two skeletons supposed to have been those of Van Horn’s partners. Joaquin Jim’s warning had not been an idle threat.

Though they kept at the search until supplies and funds were exhausted, Kirkpatrick and Colt were unable to locate the cement ledge. They did discover some ledges composed of a red cement-like material but none that were gold-bearing.

Various searchers carried on a constant hunt for the treasure during the next few years. Sometimes as many as 20 parties were in the field at once, prospecting from the desert floor to the eastern slopes of the Sierra around the base of Mammoth Mountain.

Kent and McDougall

In the summer of 1869 two men named Kent and McDougall outfitted themselves with horses and supplies in Stockton, California. They next appeared at a small settlement on the San Joaquin River at the western base of the mountains. There they hired an Indian to guide them across the mountains.

The Indian returned much later with the information that he had taken the men to the pumice mountain (Mammoth Mountain).

Kent and McDougall returned the following year and repeated their visit every year through the summer of 1877.

Late that year a man collapsed on a San Francisco street. As he lay dying in a hospital he identified himself as McDougall and related the following story.

He said that while in Arizona he had met Kent who claimed he knew of some lost treasure in California but needed help to go there. Kent hired McDougall, giving him a $1500 yearly guarantee.

When they had gone as far as the pumice mountain on that first trip Kent dismissed the guide. As soon as the Indian was out of sight Kent said he believed they were near one of the richest gold deposits he had ever seen.

He claimed he had found it in 1861 (the first year of Dr. Randall’s search) but that Indian wars had prevented his returning. From the point where they dismissed the guide, the two men went on to the headwaters of the Owens River.

Lost Ledge Found

There Kent described certain landmarks to McDougall and they began to search. Soon they found, first the landmarks, then the ledge. That summer they took out a huge sum in gold.

They melted it into bars and hid it among their belongings when they left. Each year they took out from $25,000 to $50,000, clearing in all nearly $400,000. Each time they left, McDougall said they concealed the location against chance discovery by others.

They never recorded the location or staked claims, preferring to keep the secret and avoid having it over-run with others seeking to share in the riches. Though the trip from the west over the mountains was an arduous one Kent would never risk discovery by being seen with ore in the gold thirsty camps on the desert side.

McDougall died soon after relating his story. Kent never returned nor was he ever heard from again. It is supposed that illness, or perhaps even death, intervened.

Lost Ledge lost again

The job of concealing the mine’s location must have been expertly done for it has never been found again.

There is ample proof from other sources that a rich gold deposit existed in the district. One man, trading with the Indians, was paid $300 in gold but was unable to learn where they had obtained it.

Indians coming into the camp of Benton, a day’s travel into the desert from the vicinity of the mine’s supposed location, paid for their purchases with gold but never revealed its source.

Winds, sands, and storms can do strange things to the earth’s countenance, often altering it completely. But the elements that hid a treasure can again reveal it. It seems possible that the reddish ledge, bearing its golden fortune, will someday enrich another finder.

More lost mines: