Here is a list of what to look for when panning for gold.

- Coarse Black Sands

- Hard bedrock with crevasses

- Quartz veins and stringers in bedrock

- Contact zones of different rock types

- Quartz and magnetite in the creek

- Lead pieces in the gravel

- Garnets and garnet sands

- Hard packed gravel layers

- Gravel bench areas above creek water levels

- Signs of old mining activities such as stacked rocks and tailings

Coarse Black Sands

As you are panning or sluicing gravels from creeks and rivers you will encounter black sands. Black sands are heavy and you will notice a layer in your pan that will become thicker and more noticeable as you pan out the lighter materials.

Most black sands are a type of iron oxide called magnetite and will also be magnetic. These black sands tend to concentrate with the gold on the very bottom of the pan. These are called concentrates. The black sands and gold are difficult and time-consuming to separate and are often collected together, brought back to camp or home to be carefully processed.

Most black sands are a type of iron oxide called magnetite and will also be magnetic. These black sands tend to concentrate with the gold on the very bottom of the pan. These are called concentrates. The black sands and gold are difficult and time-consuming to separate and are often collected together, brought back to camp or home to be carefully processed.

Coarse black sands are a good indicator of gold. Most black sands will be very fine. Look for areas in the creek where the black sands are large-grained. You may have to dig down before they start to show. The coarser or larger the grains of magnetite are, the more likely there will also be heavier coarser pieces of gold close by. Their presence may indicate that the creek conditions were right for a gold pocket or paystreak to form.

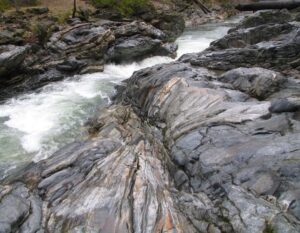

Hard bedrock with crevasses

When out panning or sluicing on small creeks and streams keep an eye out for places where bedrock is visible along the banks. Gold is very heavy and dense and with the constant sorting action of the running water, it will sink down in the gravels until it is stopped by a solid surface such as bedrock, or in some cases a clay layer.

Walk up or downstream until you find an area with exposed bedrock. Try to find areas with bedrock showing on both sides of the creek and also in the creek itself. Then you can judge the thickness of the gravel over the bedrock. You don’t want to dig down 3 or 4 feet, only to find that bedrock is still buried a number of feet below.

Walk up or downstream until you find an area with exposed bedrock. Try to find areas with bedrock showing on both sides of the creek and also in the creek itself. Then you can judge the thickness of the gravel over the bedrock. You don’t want to dig down 3 or 4 feet, only to find that bedrock is still buried a number of feet below.

The type of bedrock can be important. If it is softer material such as schist, the gold may collect on it, but during spring flooding and the rainy season, the softer bedrock can be eroded away, taking the gold with it. Ideally, a hard bedrock such as granite or gneiss, with narrow fractures, cracks, and crevasses, makes for the best bedrock gold traps. The cracks and crevasses with the best chance for holding gold will run at right angles to the creek flow, although I have encountered some good ones that ran parallel with the creek too. Every creek and placer gold district is different. You will also need some small tools like an ice pick and screwdriver to help loosen and clean out the cracks and crevasses.

Quartz veins and stringers in bedrock

Look for quartz stringers and veins in the creek and surrounding bedrock outcroppings. Quartz is the rock type most associated with gold. If the quartz shows  staining from iron oxides or contains pyrite or other sulfide minerals, that’s even better, although gold is also found in plain white quartz (bull quartz), especially in the northern US and Canada.

staining from iron oxides or contains pyrite or other sulfide minerals, that’s even better, although gold is also found in plain white quartz (bull quartz), especially in the northern US and Canada.

As these quartz veins have been gradually eroded away over millennia, gold may have been released and concentrated in the gravels of the present creek bed. Try panning or sluicing just downstream from quartz veins too, as there may be a localized concentration of gold thereabouts.

Contact zones of different rock types

Contact Zones are usually associated with hard rock gold deposits. The presence of contacts of different rock types in the bedrock of creeks and surrounding areas is a valuable indicator of the possible presence of gold nearby. If there are quartz veins near these contacts, that is an even more favorable sign.

Rock contact zones are where different rock strata come together. Different rock classes such as igneous rocks in contact with volcanic or metamorphic. There are many possible combinations. Without giving a course in geology, look for the places where bedrock shows obvious differences in coloration, texture, and hardness.

Rock contact zones are where different rock strata come together. Different rock classes such as igneous rocks in contact with volcanic or metamorphic. There are many possible combinations. Without giving a course in geology, look for the places where bedrock shows obvious differences in coloration, texture, and hardness.

Common contacts would be greenstone and shale, granite and schist, limestone and diorite, etc. I can’t overstate the importance of recognizing contact zones. Panning and sampling downstream of contact zones can uncover valuable gold-bearing gravels.

Quartz and magnetite in the creek

As you are sample panning a gravel area be on the lookout for chunks of quartz and large pieces of the black iron oxide magnetite. Sometimes there will be large rocks and even boulders of quartz and magnetite scattered throughout the creek bottom.

Both can be good indicators of gold in the area. The oldtimers used to say that if a creek or drainage area had big iron in it, then it had big gold too. Magnetite is what they meant by big iron.

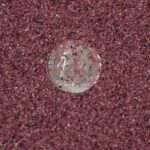

Garnets and garnet sands

A lot of creeks contain garnets, sometimes so much so that the sands in a sample pan may turn a pinkish color. Schists often  contain garnets. Schists are quite soft too, meaning garnets are released from the schists easily. Garnets are quite heavy, nowhere near as heavy as gold, but they will tend to concentrate somewhat in a pan or sluice.

contain garnets. Schists are quite soft too, meaning garnets are released from the schists easily. Garnets are quite heavy, nowhere near as heavy as gold, but they will tend to concentrate somewhat in a pan or sluice.

Because garnets are heavy, uncovering them as you pan an area, especially large garnets, may also indicate that conditions were right for gold to settle there also.

Lead pieces in the gravel

Lead and gold are similar in weight and density. Most areas in the west have seen a lot of gunfire over the years. When panning and sluicing a creek you will occasionally find a lead bullet, lead fragment, or piece of lead shot in your pan or sluice box.

If the lead pieces become numerous, the conditions in the creek that caused the lead to concentrate in the gravel may also have caused gold to concentrate with the lead, or just below it. A good sign.

Hard packed gravel layers

As you dig down into the gravel you may come across a hard-packed gravel layer. There may be gold on top of this layer, or if you are lucky, there may be gold in or at the bottom of the layer, especially if it is directly on top of bedrock. These hard-packed layers can indicate unworked or virgin ground. At the very least, they indicate the gravels haven’t been disturbed in a long time, possibly many years. These layers are usually a darker color, usually brown or possibly a light rusty orange. Sometimes a bar may be needed to break them up. A good sign.

Gravel bench areas above creek water levels

While checking along a creek for possible productive spots, scan the hills that slope down to the water. Sometimes you will be able to see gravel benches high above the present creek bed. Look for water-worn rounded boulders and cobbles in these benches. If you have time and can do it safely, climb up and bring a sample bucket of gravel down to the water to pan. Try to take the sample on bedrock, if possible. Gravel benches high up on slopes or ridgetops should always be checked if they are not inaccessible as they might actually be a leftover section of an ancient tertiary channel. If you find a tertiary channel, chances are good that it will contain gold. Possibly, a lot of gold.

Signs of old mining activities such as stacked rocks and tailings piles

In your creek reconnaissance, look for areas along the banks with hand-stacked rock walls or piles. This indicates places where the creek was worked for gold in the past, by moving large areas of rock out of the way. This may indicate that the creek, at least in that area, may have been cleaned out in years gone by. But if you are prospecting an unfamiliar creek with no mining history, stacked rocks and tailings are a sign that gold was recovered here in the past