If you have ever thought of overlanding the old Bradshaw Trail across the Colorado Desert of Southern California, I highly recommend the journey. You can travel it in either direction, but for this post, I’ve started in Blythe, California, where you exit Interstate 10, travel south through Palo Verde valley farmlands.

Crossing over an irrigation canal you start the 78 mile Bradshaw Trail proper and follow it through a pass in the Mule Mountains and down into the Chuckawalla Valley where you can camp at the BLM campgrounds of Wiley’s Well and Coon Hollow.

The Wiley’s Well area has long been a popular rockhounding spot and home to the famous Hauser Geode Beds.

Winding through some beautiful desert country you eventually reach Highway 111 about 3 miles north of the Salton Sea and the infamous Bombay Beach.

This overland route is a typical desert road and conditions can vary widely from season to season. Washboard road, sandy wash sections as well as rocky areas will all be encountered.

Come prepared and preferably with a high clearance 4×4. Don’t travel it during the summer as a vehicle breakdown can turn into a life-threatening situation.

If you would like to learn some forgotten history of the Bradshaw Trail, read the following article from the February, 1956 issue of Desert Magazine. This article goes into great detail about all kinds of history, and will add insight to your journey across this stage route of the old west.

Bradshaw’s Road to the La Paz Diggin’s

By FRANKLIN HOYT

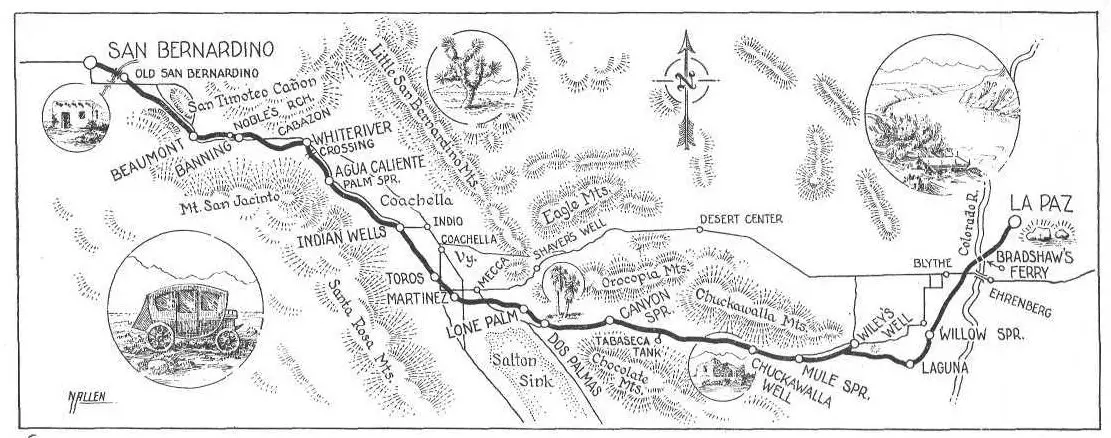

Map by Norton Allen

When word reached Los Angeles in the early 1860s that a rich placer gold field had been discovered along the Colorado River at La Paz, there was a stampede of fortune hunters. But it was a slow-moving gold rush, for the only known routes to the new field required a detour of nearly 200 miles.

Bill Bradshaw, former trooper with Fremont, solved the problem by blazing a new trail across the Southern California desert—the Bradshaw Road. For a few years, until the gold played out, it was the most-traveled route across the California desert. Today only a few of the old waterholes—and the wagon ruts—remain.

DURING THE winter of 1862 Pauline Weaver was trapping beaver and prospecting along the Arizona side of the Colorado River. About 10 miles north of where the present highway crosses the river at Blythe he found flakes of gold sparkling in the bottom of a little gulch. Panning out two or three dollars worth of the yellow metal, he placed it in a goose quill for safe keeping while he continued his trapping.

A few weeks later in Fort Yuma, Weaver proudly displayed his golden quill in all the saloons, and the Colorado River gold rush was on. By summer the Los Angeles newspapers were printing stories of 150 Americans, 500 Sonorans, and 2000 Indians working the placers near the little village of La Paz.

Reaching the mines was not easy. Perhaps the most comfortable way to do so was to board one of the ships which regularly sailed down the coast from San Francisco and around the tip of Lower California to the mouth of the Colorado River. Here the miner could buy a ticket on one of the steamers which puffed 300 miles up the river to Fort Mojave.

But the sailing ships were slow. A faster way to reach the mines was to take one of the stages which jolted and bounced out of Los Angeles to Warner’s Hot Springs and then along the route of the old Butterfield Stage line to Yuma, Arizona. A rough 60-mile trail continued north parallel to the Colorado River to the scene of the new mining strike.

An alternate route passed through San Bernardino, then over El Cajon pass and along the old Mormon trail to Fort Mojave, across the river from the present site of Needles. From Fort Mojave it was a tedious journey over the trail to the mines at La Paz.

Gold-seekers, always in a rush, wanted a more direct route from Los Angeles and San Bernardino to La Paz. Among them were impatient men who sought to blaze a new route through the San Gorgonio portal to the Salton Sink and then through the Chocolate Mountains to the Colorado River.

William D. Bradshaw of Los Angeles, who was described by writers of that day as a bold, courageous adventurer, was one of the first to recognize the need for a direct route to the rich placer diggings. Stories differ as to whether it was Chief Cabezon of the Pass Cahuilla Indians, or one of his tribesmen, who drew a rough sketch for Bradshaw, showing the water holes along the old Indian trail which extended across the desert eastward to the Colorado River.

In May, 1862, with this map as his only guide, Bradshaw rode out of San Gorgonio Pass to the river. In a few days he returned, and the San Bernardino newspaper told the advantages of the proposed new road which Bill Bradshaw announced he would build without delay.

Although wagon travel over the new route at first was difficult, it saved several days’ time over the Fort Yuma and Fort Mojave routes, and within a few months was the most popular route to the diggings.

Hubert Howe Bancroft, an enterprising San Francisco book publisher, sent one of his employees to the mines over the new road and the bookstores were soon selling a little volume entitled A Guide to the Colorado Mines. Thousands of these booklets were sold but only two copies are now in existence— one in a private collection and the other in the State Library at Sacramento.

The Guide advised the miner to provide himself with a rifle and revolver for protection against renegade Indians and if the party was large it should also take a shotgun for hunting rabbits and quail.

From Los Angeles it was suggested that the miner take the main wagon road to San Bernardino which passed through San Gabriel, El Monte, San Dimas (then known as Mud Springs) and Cucamonga.

San Bernardino was the outfitting center for travelers over the Bradshaw Road, and here horses could be secured and provisions purchased before beginning the long haul over the desert to the river.

From the Mormon village the road passed about two miles southwest of the present town of Redlands and then twisted up San Timoteo Canyon to the future site of Beaumont.

Here the Bradshaw Road through San Gorgonio Pass began.

Near Cabazon the route swung south of the present highway, crossed Snow Creek, and forded the White Water River, “a large stream of pure cold water, coming down from Mount San Bernardino, and which after crossing the road twice, runs along it for a mile and a quarter, when it bears off to the north-east, and after running a few hundred yards, sinks in the sand.”

From White Water the wagon track skirted the base of Mt. San Jacinto, following the route of the present state Highway 111 to Palm Springs, which was then known as Agua Caliente.

The road followed present Indian Avenue, one of Palm Springs’ main streets, to the Indian village located near the hot springs. Here the Guide offered the information that the Indians were Christianized and “have a large settlement, and cultivate the land, raising corn, barley, vegetables, etc., all of which they readily sell to whites, when they happen to have any on hand.

The proper place to camp here is one mile east of the village, where animals will not disturb the Indians’ patches of corn and grain, which are unfenced and where there is fine water and grass a few hundred yards south of the road.

Agua Caliente takes its name from a large spring of warm sulphur water three or four rods to the left, as we enter the village from the west. It forms a large pool, of proper depth and temperature for bathing, for which it would be well adapted were the mud cleaned out.”

After leaving the beautiful oasis of Agua Caliente, the road meandered through deep sand easterly for about 11 miles until the next water hole was reached. This was Sand Hole, “a muddy pool about 400 yards east of the road, and which, as it consists only of a collection of rainwater in a small clay basin, is always bad, and dries up early in the summer.

The next good water was six miles from Sand Hole at Indian Wells, then called Old Rancheria. In order to avoid deep washes and projecting spurs of the Santa Rosa mountains, the Bradshaw Road ran north of Indian Wells.

To reach water travelers were forced to detour two miles south where the wells were located along a sandy wash surrounded by cool cottonwood trees. These wells and the cottonwoods were washed out in the 1927 flood, but the sandy wash may still be seen a few hundred feet north of the highway.

From Indian Wells the present highway goes east to Indio, but the Bradshaw Road turned southeast along the edge of the hills through the old Indian village of Torres and on to the vicinity of the Fish Traps.

There the road turned sharply to the east and passed through the Indian settlement of Martinez where there was water in a few deep wells about a quarter of a mile from the road. “This is another Indian village, much scattered, but containing several adobe structures, makes a more pretentious appearance than the others.

Corn and sometimes barley can be had here. The place is empowered with mesquite trees, which grow with great luxuriance, the bean being gathered in large quantities by the natives. It forms an excellent food for animals when they get accustomed to its use.”

Leaving the Indian settlement of Martinez behind, the dusty road took a course almost due east through the present town of Mecca, and along the route of Highway 195 until it reached a point about four miles east of Mecca.

Here the trail continued easterly along the Mecca Hills until it reached the next watering place at Palma Seca, Lone Palm or Soda Springs, as it was sometimes called. This was 12 miles from Martinez “with heavy road most of the way.

Here there are several deep pools of limpid, but very bad water, being strongly impregnated with soda and sulphur. There is but little grass, and as animals do not like the water, it affords but an indifferent camping place.”

Although there was heavy sand most of the way, the traveler would be wise to struggle on seven more miles to Dos Palmas where there was “a deep pool of soft soda-water, but of a more palatable kind than at Palma Seca.

It discharges a large stream, which, flowing down, has caused several acres of salt grass and tule to spring up nearby. Animals do not much relish this kind of feed, and the traveler will do better to take his stock three miles to the southwest, where there are several large springs or ponds, of better water, with an abundance of cane grass, on which they will do well. Enough mesquite here, as there will be found at nearly all camping places from here on, for fuel.”

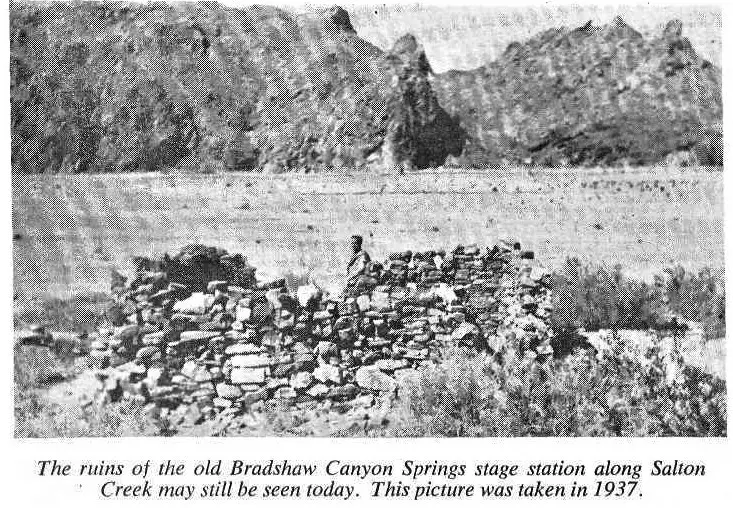

After leaving Dos Palmas the road continued east for several miles and then turned north along Salton Creek. Passing through a narrow canyon, or the Big Wash, as it was commonly called, the road then turned southeast again toward the Chocolate Mountains.

About eight miles from the mouth of the Big Wash another good camping place was reached at Tabaseca Tank, located “two miles west of the wagon road. Plenty of good water, and a moderate amount of bunch grass. No fuel.”

Between Tabaseca and the next water at “Chuckawalla” there were 18 miles of hard going, more than half of it through heavy sand. Here there was plenty of water, grass and wood, but the miner was cautioned that his horses should not be allowed to graze “as there is a species of cactus in this section of the country very abundant, which, fastening upon them when suffered to run loose, causes great trouble.

The Indians will bring enough grass to keep an animal a whole day for a couple of bits.”

Between Chuckawalla Well and the Colorado River there was a devilish stretch of 35 miles. “About one-third of the way there was heavy sand, one-third sharp, volcanic stones, hard on the horses’ feet; balance, good road. Water is reported to have been found half way across this stretch since the writer passed over.”

The river was reached below Blythe, and there were six miles of hard traveling through deep sand and around numerous sloughs until the Bradshaw Ferry was reached.

This primitive ferry crossed the river near the present highway bridge between Blythe and Ehrenberg.

Early in September, 1862, Mahlon Fairchild traveled over the Bradshaw Road, and his diary tells an interesting story of the dangers and hardships of this desert road to the Colorado River mines.

Fairchild and his companions arrived at San Pedro on the steamer Brother Jonathan, and the following day started out over the wagon road for San Bernardino, camping overnight at El Monte and Cucamonga.

From San Bernardino the miners followed the customary route through San Gorgonio Pass to White Water and Agua Caliente.

At the Indian village of Torres there was an epidemic of measles and the children were dying by the dozens. “The weather was very hot; children with skins spotted with the disease would be sprinkled with water ejected rom the mouths of the squaws to cool them off.

Generally the Indian huts were made of stout posts about five feet high with sides and roof hatched with boughs and coarse grass. Into several of these I saw them pile infant corpses with clothing and various other things and set them afire.”

At Martinez, Fairchild became disgusted with the slow-moving wagon and taking a companion with him, set out on horseback.

The first day they traveled at a leisurely pace and reached Dos Palmas in plenty of time to make camp before dark. From Dos Palmas the two men traveled in an easterly direction over the high mesas, but found no water all day and that night were forced to make a dry camp.

The following day they reached Tabaseca, where there were two springs of fair water but no grass for the hungry horses. “Here we found the shells of a large tortoise, the flesh of which had evidently been eaten by Indians.

I carried one into camp and cooked its flesh. Though there was considerable meat upon the carcass of the reptile, I admit that I did not relish it as well as I did the ordinary plain ‘jerky’ — perhaps on account of the manner of cooking.

Stopping at Tabaseca only long enough to eat and allow the horses to drink, they hurried on to “Chuckawalla.” At this spring they found water, but still no feed for the horses because the grass had been eaten by the horses of other parties which had preceded them. Their rations were almost gone so they decided to camp until the wagon arrived.

During their second day at Chuckawalla a welcome visitor arrived—a “squaw man” who lived with the Indians near Warner’s Ranch and who was traveling alone across the desert with his burro. “His business upon the desert trail I did not learn, for it was not ‘good form’ to be too inquisitive.”

He was well supplied with jerky and pinole which the Indian squaws had made from parched and pulverized grass seeds. “To us it was first rate diet at that juncture, and he gave us a liberal supply, with came seca galore, for which he would accept no coin.”

For four days they camped at Chuckawalla, impatiently waiting for the wagon. Finally, on the 7th of September, Fairchild and his companion decided not to wait any longer but to push on to the river.

Traveling mostly at night because of the extreme heat, they reached the Colorado River in two days. “We had reached Bradshaw’s ferry, opposite the town of Olivia, now Ehrenberg. The ferry was established by William Bradshaw, a former member of Fremont’s expeditions.

A rude boat capable of carrying wagons and a limited number of animals, attached to a rope spanning the stream, the current being the propelling power, comprised the affair.

On the 10th day of the month, the wagon and party we had left at Martinez arrived, all well, but with animals pretty badly used up.”

It was several months before the Bradshaw Road was universally accepted as the best way to reach the mines. Advocates of the Fort Mojave route claimed that the new road was dangerous because of the scarcity of water and the chances of getting lost.

During the summer of 1862 the new road suffered a severe setback when the Charles Yates party of five men, and the Garrett family of father, mother, and five children, became lost on the Bradshaw Road and all died of thirst.

Commenting on these tragedies, a letter in the Los Angeles Star said: “I traveled on the well known road to Fort Mojave. If the parties that were defeated on the Cabazon Desert had gone by the Mojave route, they would now have been at the mines, and none would have lost their lives.”

The new road became accepted, however, and by the fall of 1862 most of the miners were using this route. Bradshaw did his part in popularizing the road by giving enthusiastic interviews to the newspapers and by guiding miners over the new route.

In August of 1862 he personally led a party of 150 miners from San Bernardino to La Paz. Freight wagons and pack trains began operating over the road soon after it opened, but it was not until early in the fall of 1862 that the first “coach and six” came dashing into La Paz.

This was the first stage of a new line from Los Angeles to the Colorado River, established by Warren Hall and Henry Wilkinson who were working for the Alexander Company of Los Angeles.

With more than $5000 in gold dust in the “boot,” the stage raced back to Los Angeles in four days, setting a new record.

For a few weeks the stages operated regularly from Los Angeles to the river, usually carrying a full load of miners who were willing to pay the $40 fare.

Concord coaches were built to accommodate nine passengers inside, and six more could be perched on top, but more than double this number were sometimes crowded on. It is said that one stage left San Bernardino with 35 passengers, “not counting the driver and a Chinaman.”

About a month after the first coach clattered into La Paz, Hall and Wilkinson were murdered by a disgruntled station keeper near Dr. Smith’s ranch in San Gorgonio Pass.

The employee was arrested and brought to trial in San Bernardino, but the jury believed his story that he had shot in self defense and he was acquitted.

After the death of Hall and Wilkinson the Alexander Company abandoned its ill starred venture. For the next few years open freight wagons continued to carry cargo and passengers to the mines, but apparently there was no regular stage line in operation.

For a short time during the winter of 1867 Banning and Company, one of the leading Southern California transportation companies, tried to use the route through San Gorgonio Pass for its stages to Yuma.

This new route followed the Bradshaw Road to-a point about one mile east of Dos Palmas where the road to Yuma branched off toward the south.

Late in February Pat Murray, one -of the drivers for Banning and Company, left Yuma over the new route with one passenger and some freight. Halfway between Yuma and Dos Palmas he lost the trail because a station camp had been removed, and they wandered for three days without water.

In desperation the horses were turned loose, and they led Pat and his passenger to Frink’s spring.

The newspaper account of this near tragedy said that it was understood “that the stock of Banning and Co. have been removed from the newly laid out road to Fort Yuma branching from Dos Palmas, on the line to La Paz.

It is unnecessary to say that the road was utterly impracticable, a desert country of nearly a hundred miles rendering it impossible for stock to travel, with sand up to the hubs.”

Uncle Sam gave his approval to the Bradshaw Road in 1868 when the Post Office Department announced that it had abandoned the old mail route from San Bernardino to Prescott, by way of Cajon Pass and Fort Mojave.

A new contract was awarded for carrying the mail over the Bradshaw Road to La Paz, Wickenburg and Prescott; mail for Fort Yuma was taken off at La Paz and sent down the river on the steamers.

Until the completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad, almost a decade later, buckboards and light wagons continued to carry the mail over this route to western Arizona.

Compared with other desert roads of the west, the Bradshaw Road was well supplied with water, the average distance between water holes is about 10 miles.

Between Chuckawalla and the river it was necessary to travel 35 miles without water, but later a well was developed half-way across this stretch.

Along the old Mormon trail between San Bernardino and Salt Lake City the distances between watering places were much greater. In one place there was a pull of 55 miles without water of any kind.

With all of its advantages the Bradshaw Road was never very successful. Articles in the San Bernardino newspapers complained that it ran in an “angling, crooked, roundabout course, over deep sands, and entailing 40 miles of unnecessary travel.”

In 1872 Franc V. Bishop wrote a letter to a friend who asked the best way of getting to the mines. It was easy, he said; just take the stage from Los Angeles to San Bernardino, and from there to Ehrenberg and you are in Arizona.

“You would have a pleasant ride to San Bernardino, see a queer pretty town and lots of Mormons, but having seen it had better return to Los Angeles, for between you and the Colorado lie 300 miles of desert travel, and more than likely there are no covered stages running. So take the steamer.”

Clarence King rode a mule across the Bradshaw Road from La Paz to San Bernardino in the spring of 1866.

He later wrote that the road was not well marked and that he had difficulty following it in places. “Indian trails led out in all directions, and our only clue to the right path was . . . two conspicuous mountain piles.”

He camped at the oasis of Palm Springs where there were two palm trees and near the palms a “low, deserted cabin with a wide, overhanging flat roof, which had long ago been thatched with palm leaves.”

During the 1870s the wife of an army officer stationed in Arizona traveled by stage from Tucson to San Francisco over the Bradshaw Road.

When the coach pulled up at the Chuckawalla station for lunch they found that Indians had made a raid and gotten away with most of the food during the night. The meal was cooked and served by the station keeper who stood at her elbow with a “battered, grimy, and unclean looking coffee-pot.”

He asked, “will yer have coffee, tea, cocoa, chocolate, or milk?” Then before she had a chance to reply he added, “YerU have to take coffee, dam’it, for that’s all there is.”

In the spring of 1876 the Southern Pacific Railroad finished laying its tracks down the San Gorgonio Pass to White Water.

Arrival of the railroad spelled doom for the Bradshaw Road, but for a few months it had more traffic than at any time during its brief history.

Instead of taking the steamers around Lower California, many travelers bound for Arizona found it more convenient to take a Southern Pacific train out through San Gorgonio Pass to the end of the line where they could board “new first-class coaches” for Ehrenberg, Wickenburg, Prescott, Phoenix, Florence and Tucson.

The stages left two or three times a week, depending upon the arrival of trains from Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the trip to Prescott took four days.

By the spring of 1877 the railroad reached Pilot Knob and the stages to Arizona abandoned the Bradshaw Road and began running their coaches into Yuma. All along the new railroad towns began to spring up—Beaumont, Banning, Indio, Coachella, Thermal, Mecca.

With the building of these towns new roads were constructed and old roads improved. Some of these new roads followed the Bradshaw Road, but stretches of the old stage route were abandoned.

In some places only a track remains—in others drifting sand has covered the road until not a trace is left. From Dos Palmas to the Colorado, Riverside County maps still show the Bradshaw Road as an unimproved road, still traveled by a few hardy prospectors and desert rats with their burros and desert automobiles.